*Written for Interactions Magazine*

The day after Steve Jobs died, my friend Rich Binell, another Apple alum, asked, “Why did Steve Jobs’ passing affect us more than the passing of other notable people?” Of course, Jobs changed the world, and many of us were moved by his work.

How did he do it?

Parts of the story are familiar. While still in high school, Jobs learned from Bill Hewlett how an individual can expand possibilities. His experience with Hewlett, courses at Reed College, and mentoring by PR maven Regis McKenna also expanded Jobs’ sense of “quality” and its importance. Jobs seems to have understood quality much as Robert Pirsig did—as a consequence of making and as an effect of process. (Pirsig published *Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values* two years after Jobs graduated from high school. Pirsig’s book was popular, and perhaps Jobs read it around that time.

Jobs’s BMW motorcycle suggests a connection.)

Jobs recognized quality during his visit to Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), where he first saw computers displaying a forerunner to what has become, with his help, a standard computer interface. Lisa, Macintosh, and NeXT were amazing attempts to bring that quality to a broader audience. The fully automated Macintosh factory in Fremont and the 1984 Mac introduction were also expressions of quality, but the Lisa, Macintosh, and NeXT computers themselves fell short.

My point is: During his first reign at Apple and his time at NeXT, Steve Jobs did not build a successful product. Products led by others, the Apple II, the Macintosh II, and the Laserwriter II kept Apple alive.

When Jobs returned to Apple, he seems to have changed. iPod, iPhone, and iPad followed a smoother path than his earlier products.

What was different? What did Steve Jobs learn during his years in the wilderness?

What can he teach us about designing? I see three principles.

**Whole systems thinking**

Jobs’ concept of systems matured. Apple, NeXT, and Pixar were never just hardware companies, but in their early phases, their notion of system was limited to hardware and software integration, closely coupled with marketing communications. Later Apple’s systems thinking grew to include the integration of products, services, content, distribution, communications, and developers—the creation of ecosystems. Apple’s systems approach shows through in many places, such as the company’s online presence, its retail stores, and its frighteningly efficient supply chain (which had been notoriously poor until Steve Jobs hired Tim Cook to fix it).

**Broad, deep teams**

During his second reign, Jobs made Apple’s product development process self-sustaining. Gone were the pirate flags and death marches; replaced by a healthier environment—broad and deep expertise, a measure of respect, and a culture which managed to retain many members for ten years or more, enough time to build experience and trust. During the same period, Apple’s prototype iteration cycle shrank to one-third or one-quarter of the industry norm.

**Design conversations**

Perhaps most important: Jobs created partnerships with designers.

During Apple’s early years, Tom Suiter, who had been at Landor, showed Jobs that it is possible to build a world-class in-house graphic design team. (Jobs didn’t think it could be done but let Suiter try.) Suiter’s organization survived Jobs’ departure (and Suiter’s). The organization also survived the long interregnum, and upon his return, Jobs developed a new partnership with creative director Hiroki Asai, who now manages Apple’s graphic design team.

As Jobs developed Macintosh, he forged close (but short-lived) partnerships with several designers, most notably perhaps, with Susan Kare, who was responsible for the appearance of the original Macintosh UI. Unfortunately, the original Macintosh team disbanded soon after Jobs left Apple, though members of the team went on to make other significant contributions, such as HyperCard (Bill Atkinson) and Newton (Larry Tesler).

Very early, Jobs began a long partnership with Lee Clow, creative director at Chiat-Day, Apple’s advertising agency. Clow was the art-director who collaborated on the famous *1984* commercial with writer Steve Hayden. On Jobs’ return, Clow led the teams that created the iconic Think Different, iMac, and iPod campaigns.

In the early days, Apple out-sourced most of its product design, principally to frog.

Jobs continued to out-source product design at NeXT. (Jobs left Apple in 1985; in 1989, Bob Brunner joined Apple, building a world-class in-house product design team.)

Jobs’ later partnership with Jonathan Ive (hired by Brunner) is well known. What’s less well known is how Jobs and Ive worked together and how they worked with the rest of the product development team. We get this tantalizing clue from Jonathan Ive, “Much of the design process is a conversation, a back-and-forth as we [Jobs and Ive] walk around the tables and play with the models. [1]”

That goes to the heart of my point about Jobs’ partnerships with designers. He was setting up conversations. These conversations are key to Job’s view of what design is. “In most people’s vocabularies, design means veneer. It’s interior decorating. It’s the fabric of the curtains and the sofa. But to me, nothing could be further from the meaning of design. Design is the fundamental soul of a man-made creation that ends up expressing itself in successive outer layers of the product or service [2].”

Understanding the soul of a product (or of an organization) requires conversation—about what you believe in, about fundamental values, about quality. These ideas must be argued and agreed. Likewise, expressing the soul of a product requires still more conversations, still more argument and agreement. At this level, design is conversation.

**Other leader-designer partnerships**

While it may be “magic”, the leader-designer-partnership model is not unique to Apple. It’s an old pattern. Well before Steve Jobs partnered with Jonathan Ive, leader-designer partnerships often led to great things. At Pixar, co-founder Ed Catmul has an extraordinary partnership with director, John Lasseter. (Exposure to their partnership had to have had a profound affect on Jobs.) At IBM, CEO Tom Watson, Jr., partnered with Eliot Noyes, who in turn collaborated with Richard Sapir, Paul Rand, and a host of other great designers and architects, a story wonderfully chronicled in Bruce Gordon’s authoritative monograph on Noyes [3]. At Container Corporation, CEO Walter Paepke partnered with Herbert Bayer. Adriano Olivetti partnered with Marcello Nizzoli.

Artur and Erwin Braun partnered with Dieter Rams.

At Herman Miller, CEO Max Dupree partnered with George Nelson, who in turn collaborated with a host of great designers. At CBS, CEO William Paley partnered with William Golden, and Paley’s successor, Frank Stanton, partnered with Golden’s successor, Lou Dorfsman, illustrating that the model can live beyond founders.

It’s not an all-guy thing, either. Hans Knoll partnered with (and later married) Florence Schust. Martha Stewart partners with Gael Towey and Eric Pike.

There are many similar examples. In these partnerships, not all the leaders are founders, though most are. (Tom Watson, Jr. was the son of IBM’s founder.) The key trait is that the leader identify closely with the company and feel an extraordinary responsibility for it, perhaps even seeing the company as an extension of himself or herself. Unfortunately, non-founder or non-family managers don’t often have the same passion, or perhaps they are simply more realistic about their relationship to the company. Either way, hired managers rarely form close partnerships with designers or support strong design organizations. (Frank Stanton at CBS was an exception, and we instinctively recognize that Tim Cook faces a challenge as Jobs’ successor.)

The CEO-designer partnership model shows up in just about every company that creates great design over a sustained period. The consistency of this pattern suggests that it is repeatable—and learnable. It also suggests that claims about the effectiveness of design thinking (absent some larger conversation and the partnership that sustains it) are exaggerated. While valuable, ethnography plus rapid prototyping gets you only so far; they cannot deliver high-quality design and sustain it over a long period without a special kind of support from the head of the organization.

It is the larger conversations—the conversations about goals and means, about needs and possibilities, about context and constraints, about what needs doing and why—which designers are good at facilitating. Good designers “force” these conversations, because good results require them.

Good consultants nourish these conversations, too. Great advertising agencies can also spark them and sometimes sustain them. But the conversations may work best when most of the parties are inside the company.

Certainly, the conversations require a special kind of passion and commitment from the CEO. And that may be Jobs’ greatest lesson.

**Where can the conversation go wrong?**

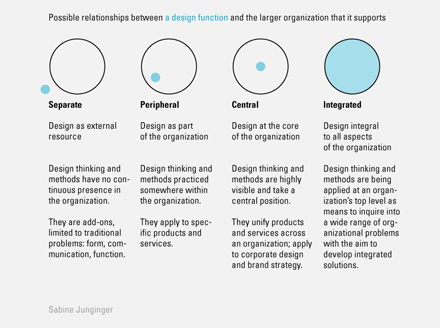

Sabine Junginger has proposed a model illustrating four types of relationship, which a design function may have with the larger organization that supports it [4].

Junginger’s model suggests a progression of states from separate to peripheral to central to integrated. One might imagine that Apple has achieved the fourth state, creating a design culture and tightly integrating design throughout the organization.

Though the model helps us classify organizations,

it also raises questions: How does an organization move between states? How does a company’s design capability improve or degrade?

These questions are practical—with answers worth perhaps billions of dollars. Consider some examples. Samsung’s chairman, Kun-hee Lee, understands the value of design and has made it central to the company [5]. Why, then has Samsung failed to achieve the same level of design excellence as Apple? We might also ask what has happened to Sony, once a design leader? And what of IBM, which once had the best-managed design program in the world?

Despite considerable effort and expense, Samsung has failed to become a design leader, in part because its chairman does not take an active role in product development and design and also because it has no executive-level creative director. (Last year, Samsung flirted with hiring Chris Bangle, BMW’s former design chief [6].

Samsung does have several executives responsible for design, but for the most part, they function as personnel managers and provide little creative direction.) Chairman Lee’s hands-off role and the lack of executive-level creative direction mean that Samsung has few leader-designer partnerships and few senior-level design conversations.

One exception is Gee-sung Choi, who as head of the TV group forged a close relation with its product designers and especially Seung-ho Lee, which resulted in the successful Bordeaux product line [5]. Unfortunately, that partnership has not continued. However, Choi has become Samsung’s Chief Design Officer (among other responsibilities) even though he is not trained as a designer.

In contrast to Samsung’s Chairman Lee, Sony founder Akio Morita took a very different role involving himself deeply in product development. Sony’s current chairman, Howard Stringer, has taken a managerial approach to products, with predictable results: Sony has slipped from its position as an innovator and design leader.

Something similar happened at IBM after Tom Watson, Jr., retired, though the change took much longer. The design management structure that Watson and Noyes put in place served the company well for many years. And even now, IBM has a remarkable system for coordinating internal and external conversations between design resources. But the design conversations are several levels below the CEO, mainly within Jon Iwata’s marketing organization. One IBM insider remarked that the last CEO, Sam Palmisano, “was a sales guy not much interested in design.” Seven CEOs after Watson and Noyes, design at IBM is still well managed, but without the level of conversation that took place between those two, design is no longer a strategic advantage for IBM.

**Models of design conversations**

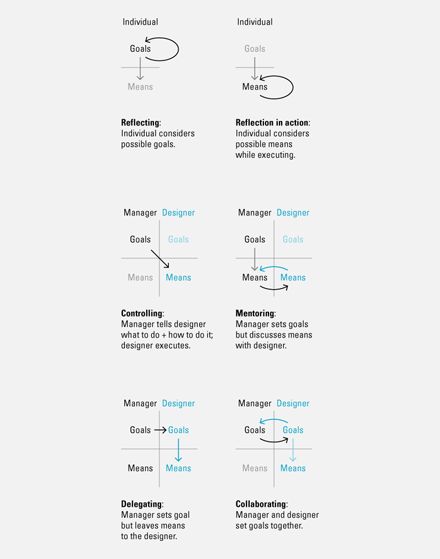

A conversation between a CEO and his or her design director may cover many topics, but the conversations take only a few forms.

The possible forms are the same for any manager-designer conversation. An individual may have a conversation with himself or herself about goals (Reflecting) or about means (Reflection in action). A manager may control an employee, directing what is done and how it is done.

This boot-camp style may sometimes be appropriate for “raw recruits” but is out of place in senior management (Controlling). When necessary, a good manager will mentor or teach an employee, discussing possible means for achieving a goal (Mentoring). And often a good manager will delegate to a willing and able employee, “merely” setting goals and leaving the employee free to choose a means of achieving them (Delegating).

But only one form of conversation leads to a partnership, to deep trust, and ultimately to innovation and a sustained period of good design. Such conversations are principally about goals—about beliefs, about values, and about quality (Collaborating).

Steve Jobs learned to foster such conversations. So did Jon Lasseter, Eliot Noyes, and the others mentioned here. Their conversations cover all aspects of design, not just physical product design, but also architecture, film making, designing for interaction and service as well as communications design. These conversations are the essence of product management and brand management. This legacy is easy to overlook. It’s easy to imagine a special magic, and in a way it *is* a special magic. Why else would it be so rare?

What other magic did Steve Jobs learn? He guarded Apple’s development process closely. Now that he’s gone, I hope we will come to understand his process better.

That would be a truly world-changing legacy.

I’ve outlined three principles, putting special emphasis on the last:

- Whole systems thinking

- Deep, broad teams

- Design conversations

What have I missed?

**Endnotes**

1: Isaacson, W. *Steve Jobs*. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 2011, 346.

2: Steve Jobs quoted in “Apple’s One-Dollar-a- Year Man”, *Fortune*, January 24, 2000. http:// money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_ archive/2000/01/24/272277/index.htm

3: Bruce, G. *Eliot Noyes: A Pioneer of Design and Architecture in the Age of Modernism*. Phaidon, New York, 2006.

4: Junginger, S. *Design in the organization: Parts and wholes*. Design Research Journal, 2, 9 (2009), Swedish Design Council (SVID), 23-29.

5: Freeze, K. and Chung, K-W. *Design strategy at Samsung: Becoming a top tier company*. Design Management Institute Case Study, DMI, Boston, 2008.

6: Stevens, R. Chris Bangle, former BMW designer, bringing his deconstructivist ways to Samsung devices? *Endgadget* (March 12, 2011); http://www.engadget.com/2011/03/12/ chris-bangle-former-bmw-designer-bringing- his-deconstructivist/

**About the Author**

Hugh Dubberly manages a consultancy focused on making services and software easier to use through interaction design and information design. In the past he was vice president of design at Netscape and spent 10 years at Apple, where he managed graphic design and corporate identity. Dubberly also founded the interactive media department at Art Center and has taught at CMU, IIT Institute of Design, San Jose State, and Stanford.

**About this column**

Models help bridge the gap between observing and making—especially when systems are involved (as in designing for interaction, service, and evolution). This forum introduces new models, links them to existing models, and describes their histories and why they matter.

— Hugh Dubberly, Editor

6 Comments

Bill Carley

Apr 8, 2013

7:59 am

Hugh – You nailed it! Nice retrospective and well crafted summary of Apple’s “ju-ju”, as well as the early peer influences to Apple’s development. Being an early Apple devotee, I have always thought that this holistic view of Design requirements, from the User’s Perspective, is one of the key legacies of Steve Jobs. Let’s face it: Supply Chain is a tough nut for everyone, and still a perplexing domain for most major manufacturers.

Richard M.

Aug 8, 2013

9:01 am

Great insightful read, thank you very much.

Haniff din

Oct 15, 2014

7:09 pm

I think you miss a very very key element.

Passion.

Jobs had a passion for creating a generation leaping product, and a genuine passion for how technology can be made easier and cool to use.

You can see this in all the interviews on you tube.

More importantly they were designed and creating a product before it was technically possible. The ipad idea and Siri idea were all thought about decades before they became real.

This generation leaping and imagining how technology could be is the “futurist” side which is key first, the design comes later.

Now how many CEOs have a passion to genuinely create a generation leaping product ?

I way say right now none.

That’s the difference.

You can’t teach that passion. You are born with it.

It’s always the crazy outsider that makes the generation leap.

Design is simply part of the function to make that idea real. You just talent for that, which he did.

The talent in no way had the futurist vision first.

Like einstien said , imagination is more important than knowledge.

It’s the imagination, ideas and willingness to take that leap / risk is what is missing in CEOs now.

Jason Vu

Aug 11, 2015

9:35 pm

Love the part about design conversations. Conversations to me mean passion and you can’t stop thinking about it until you find the best design. Great write up.

MD Eckersley

Sep 15, 2015

11:54 am

Thanks (again) Hugh. You rock!

Atilla

Oct 12, 2021

8:33 am

A little late to this article but a great discovery (I fell into a wormhole reading an article by my RISD tutor Paul Kahn on COVID visualisations and ended up here!)

Excellent insight into the organisation-design-designer relationship. Thank you!