-

Dubberly Design Office

2501 Harrison Street, No. 7

San Francisco, CA 94110 -

415 648 9799 phone

415 648 9899 fax

Articles

Reframing health to embrace design of our own well-being

*Written for Interactions magazine by Hugh Dubberly, Rajiv Mehta, Shelley Evenson, Paul Pangaro.*

*Editor’s Note:

*

Improving healthcare is a wicked problem [1]. Healthcare’s many stakeholders can’t agree on a solution, because they don’t agree on the problem. They come to the discussion from different points of view, with different frames. Wicked problems can be “solved” only by reframing, by providing a new way of understanding the problem that stakeholders can share [1]. This article describes a growing trend: framing health in terms of well-being and broadening healthcare to include self-management. Self-management reframes patients as designers, an example of a shift also occurring in design practice—reframing users as designers. The article concludes with thoughts on what these changes may mean when designing for health.

*—Hugh Dubberly*

Designing for Service: Creating an Experience Advantage

Design

—

We are surrounded by things that have been designed—from the utensils we eat with, to the vehicles that transport us, to the machines we interact with. We use and experience designed artifacts everyday. Yet most people think of designers as only having applied the surface treatment to a thing conceived by someone else. Eli Blevis created an illustration to emphasize the gulf between the general public’s notion of design and designer’s views of design (Blevis et al., 2006) (see Figure 19.1).

The Language/Action Model of Conversation: Can conversation perform acts of design?

*Written for Interactions magazine by Peter H. Jones.*

*Editor’s Note:

*

*In last year’s January + February issue Usman Haque, Paul Pangaro, and I described several types of interaction—reacting, regulating, learning, balancing, managing, and conversing. In the July + August 2009 issue, Paul Pangaro and I described several types of conversing—agreeing, learning, coordinating, and collaborating—and we proposed using models based on Gordon Pask’s Conversation Theory as a guide for improving human-computer interaction. Peter Jones responded, noting that there are other models of conversation and prior work in bringing conversation to human-computer interaction in particular Winograd and Flores 1986 work with The Coordinator. We agree on the importance of The Coordinator and invited Peter to outline the history of models of conversation and their relationship to HCI. His response follows.*

*—Hugh Dubberly*

Bio-cost: An Economics of Human Behavior

*Written for Guest Column in ASC / Cybernetics of Human Knowing*

Much of human behavior is directed toward goals: finding food, selling services, curing cancer, making meaning.

Achieving goals requires action. Action requires effort. Effort requires energy and attention applied over time. Effort overcomes obstacles. Obstacles tax our patience, sap our resolve, and cause us stress.

Using Concept Maps in Product Development: Preparing to Redesign java.sun.com

a case study from

*Exposing the Magic of Design: A Practitioner’s Guide to the Methods and Theory of Synthesis*

edited by Jon Kolko

Oxford University Press

Dubberly Design Office consults on development of software and services. We follow a user-centered process that often involves mapping. We use concept maps to represent factors that influence the product development process. We regularly map user goal structures and user interactions; business models and resource flows; and hardware and software infrastructure and information flows. Increasingly, we are called on to map data models and content domains.

A Model of Mobile Community: Designing User Interfaces to Support Group Interaction

*Written for Interactions magazine by Youngho Rhee and Juyoun Lee.*

*Editor’s Note:

*

*This article proposes several models of community, including a model of “mobile community”—an extension of physical community merged with online community. The authors also provide examples of how these models have contributed to the development of community applications in their work at Samsung.*

*—Hugh Dubberly*

Building Support for Use-Based Design into Hardware Products

*Written for Interactions magazine by Tim Misner.*

*Editor’s Note:

*

*Use-based design is a new model of product development. It is a process of measuring user behavior and applying the resulting data to improve the next version of a product—creating a feedback loop between user and designer. (We might refer to the process as data-driven design, but that term has another meaning among software developers.)*

*Basing design decisions on customer behavior has roots in mail-order catalogs of the late 19th century, such as Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck. Use-based design grew along with direct mail in the mid-20th century. More recently, the Web created opportunities for collecting data on user behavior. Google is famous for driving decisions with use data. But few designers have experience in basing decisions on data, and many are still uncomfortable with the practice.*

10 Models of Teaching + Learning

Here we have collected 10 models,

each of which answer the questions:

What is teaching?

What is learning?

Each model is partial—incomplete.

But each provides a point of view, a frame.

The models are arranged from simple to complex.

They begin with two open-loop processes.

Model 1, the famous he Nuremberg Funnel,

frames teaching as content delivery.

In Model 2, Shannon provides a richer view of communication,

adding encoding/decoding and noise to the process.

Models 3 + 4 close the loop,

introducing feedback to the process—

first external assessment and then self-regulation.

Models 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 add other levels of feedback,

introducing second-order systems—

first more levels of external assessment,

then systems for helping organizations learn

and systems for generating knowledge within a discipline,

and finally framing students as second-order systems.

Model 9 + 10 are about conversation—

defined as interaction between two second-order systems—

first a conversation between teacher and student

and then more broadly a conversation between

a community of learning and a community of practice.

We acknowledge that the collection is incomplete,

and we invite others to [share their models](https://www.dubberly.com/contact “Share a model”).

We offer the collection based on the belief that

teaching + learning are fundamental

to creating the sort of society

in which we would all like to live—

but that current processes of education are far from ideal.

We also believe that improving education

(defining and reaching a desired state)

requires understanding the current state.

We believe models may aid discussion

about where we are and where we should go.

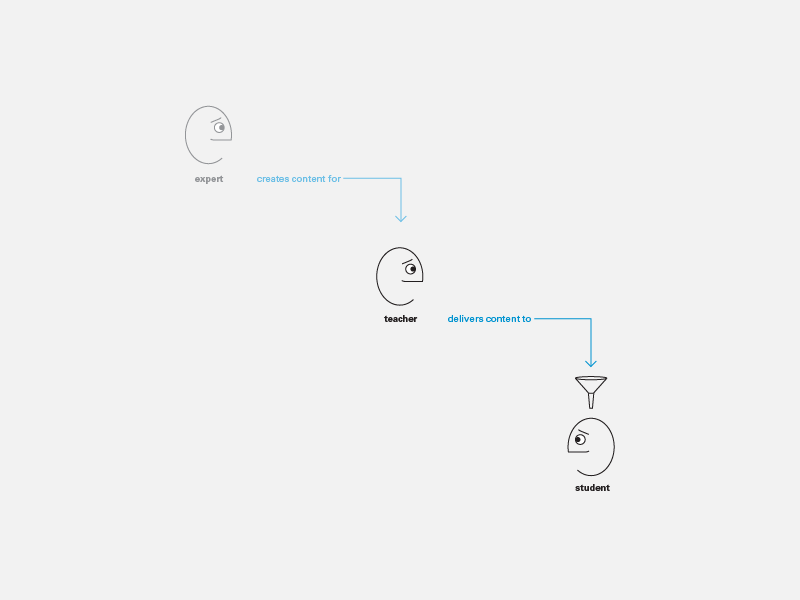

**1. Nuremberg Funnel**

Teaching as content delivery

This model claims that learning is simply a matter of passively “absorbing” what the teacher presents, and that every student is capable of “taking in” content no matter what the form or subject.

This model separates content from teacher and implies teachers are interchangeable (likewise students).

It also suggests content can be created by an author (expert) independent of teachers and students.

Of course, sometimes teachers are experts.

Delivery of a message does not ensure learning:

– The message may not be received.

– Receiving may not be the same as understanding.

– Understanding may not be the same as learning.

– Students may not learn (or may not study) unless they foresee a penalty (or reward) for doing so.

– In order to understand a second message, students must often understand a first message. (This suggests that learning “builds on a foundation.”)

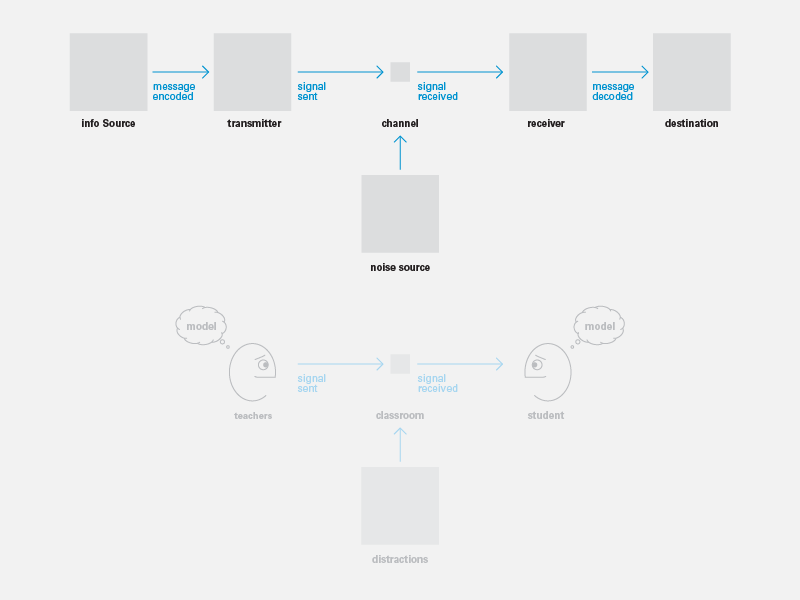

**2. Shannon’s Model of Communication**

Introducing the problem of noise in transmission

This model assumes sender + receiver share a common vocabulary (which makes encoding + decoding possible); but a goal of education is to expand students’ vocabularies, a process this model does not describe.

Shannon explained how adding redundancy in a message can compensate for noise in a channel. This is analogous to saying that repetition is sufficient to compensate for failure of a student to correctly decode a message.

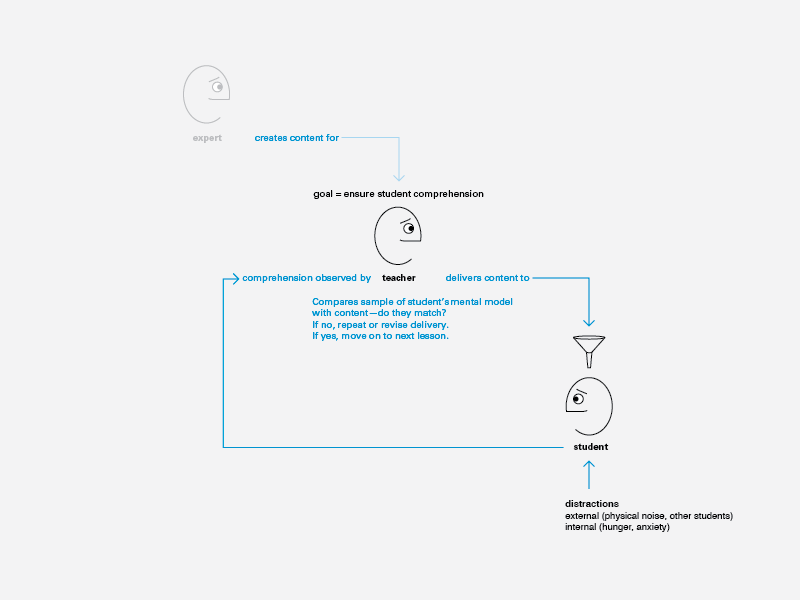

**3. Assessment: External Regulation**

Checking that students received “the message”

This model is like any feedback system. For example, a captain gives the order to dock the ship at port (sets a higher level goal). The pilot sets a course toward port by moving the wheel and then watching to see if the ship veers off because of wind or tide. If so, the pilot compares the current heading with the desired heading and adjusts the wheel accordingly. At a lower level, changing the heading translates into setting a new goal for the “wheel angle” (or rudder angle).

This model assumes teachers have a responsibility to ensure that their students learn.

Teachers organize a series of “lessons” (lectures, exercises, etc.) which lead to mastery of a higher-level “unit”.

When students demonstrate competence in one lesson, the teacher then moves on to the next.

SRA is an example of this model applied first to teach reading and later to other subjects.

One issue with this model is that both teachers and students are accountable to agents outside the model.

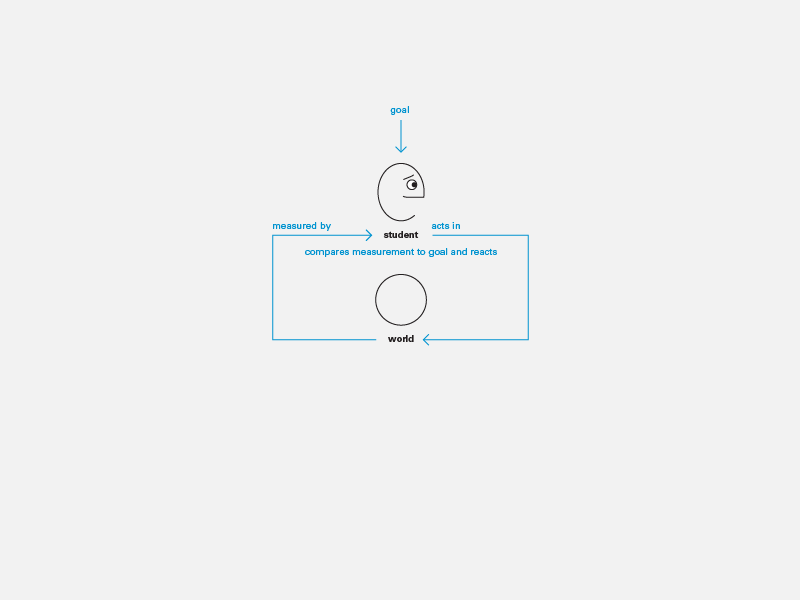

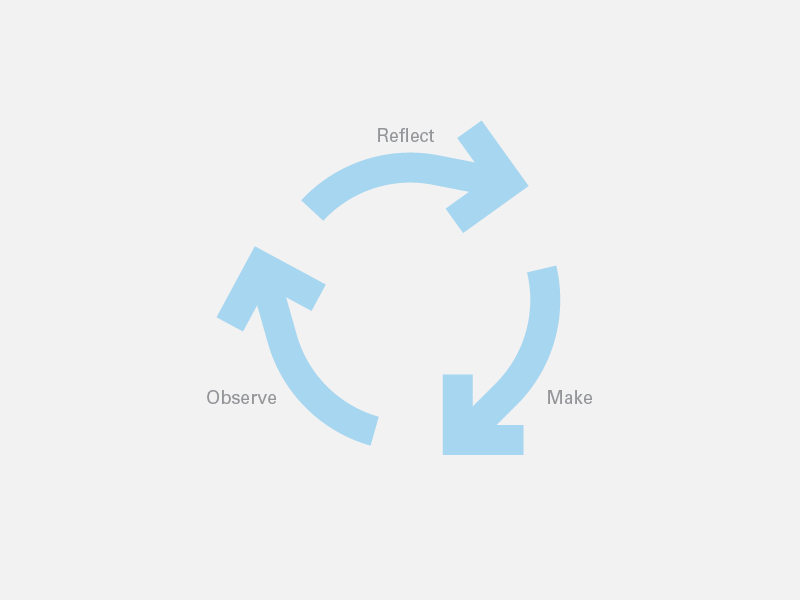

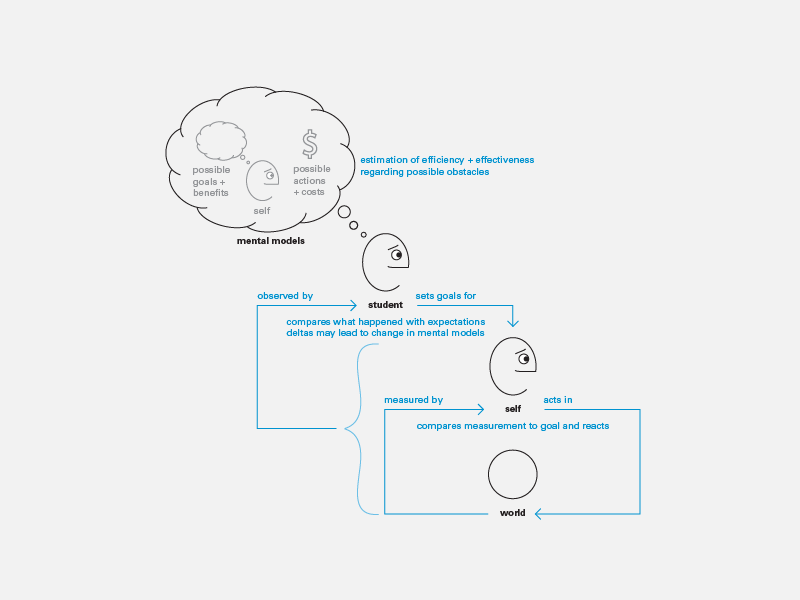

**4. Self-regulation**

Learning by acting in the world

Students learn by acting in the world, measuring the effects of their actions, comparing those effects to their goals, and modifying their actions to bring the effects more in line with their goals.

“Acting in the world” could be operating a simulation, or teaching back to the teacher, or teaching each other.

This model frames students as seeking to maintain a relationship with their environment. It argues that learning cannot be “dis-embodied” and is not merely a matter of mind or an exchange of messages.

However, learning is not mere regulation; a float valve does not learn. First-order systems cannot change goals or strategies.

By framing learning as self-regulation, we can see its relationship to design and the creative process.

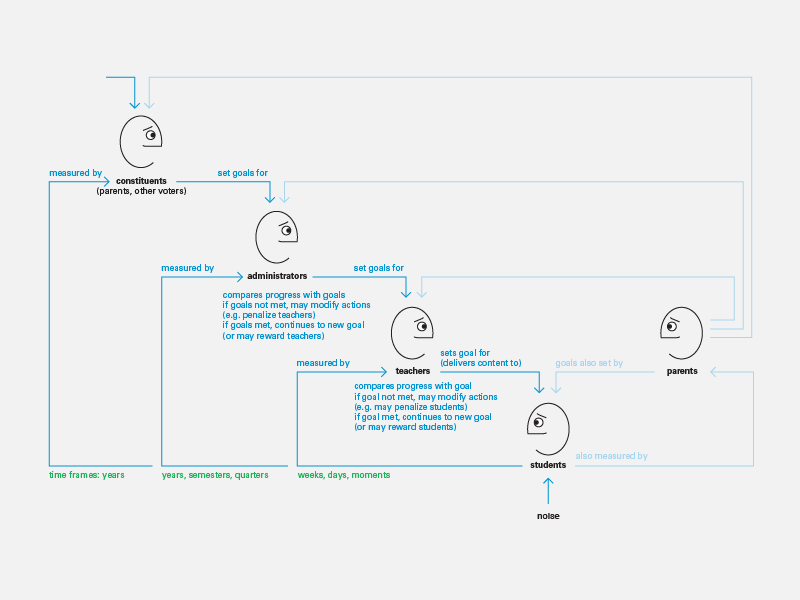

**5. Second-order Assessment**

Regulating the regulators

Institutions are complex systems with many levels of feedback, operating across many time scales.

Constituents (e.g., parents) regulate administrators.

Administrators regulate teachers.

Teachers regulate students.

Students receive feedback on their performance from teachers and parents.

Likewise, teachers and administrators may receive feedback on their performance from parents—and even from students.

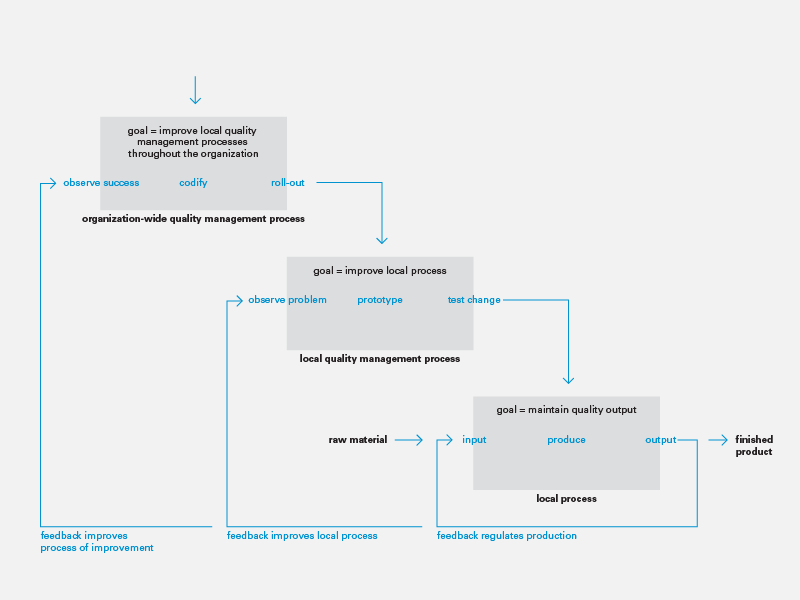

**6. “Boot-strapping:” How Organizations Learn**

Improving the way we improve

The quality cycle (plan, do, check) is a first-order feedback loop—a process used by quality teams to improve the way they implement a basic process. (Basic processes are likely to include self-regulation). An additional process monitors the work of all quality teams; identifies local solutions and processes that may have wider value; and distributes them to other parts of the organization.

Walter Shewhart formalized the quality cycle, and his protege Edward Demming made it famous. Doug Engelbart refers to “the process of improving ‘the process of improving’” as “boot-strapping”; boot-strapping is a component of what Peter Senge calls a “learning organization.”

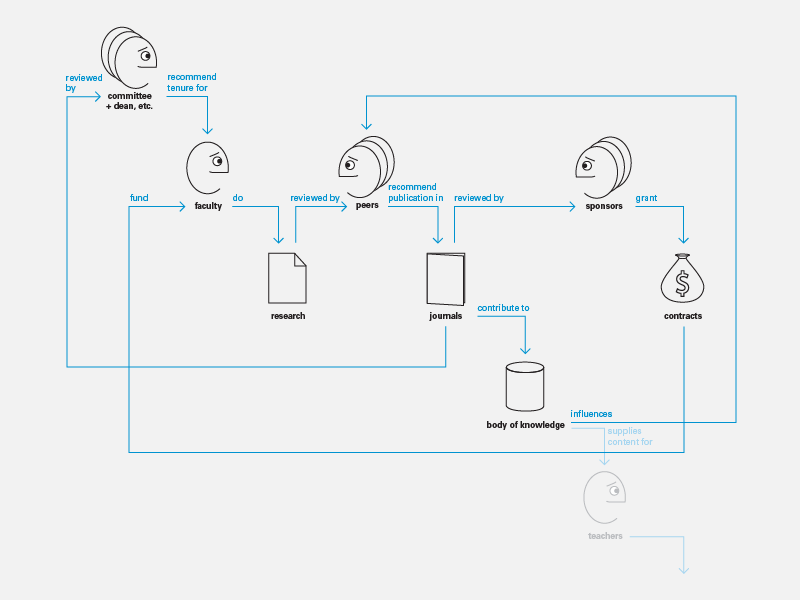

**7. Feedback Supports Knowledge Creation**

Aligning goals + incentives

Faculty seek long-term financial stability, which makes tenure attractive. Tenure requires publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Journals seek new ideas based on new research. Research requires funding, which is made more likely by previous funding, research, and publishing.

**8. Students as Second-order Systems**

Reflecting on goals + means while acting

Students have a mental model of themselves, a model of their goals, and a model of possible actions (process for achieving goals) which include effectiveness (how well an action achieves a goal) and efficiency (how easily an action achieves a goal).

Students observe themselves acting in the world and may reflect on the value (= benefit – cost) of strategies (lower-level goals + actions) in achieving higher-level goals.

In the process, they may change goals within a specific strategy or even change strategies.

Reflecting on actions changes their mental models, in particular changing assessment of effectiveness and efficiency.

This model can describe experimenting and designing. It posits learning as assessment of our actions,

which causes us to revise our mental models.

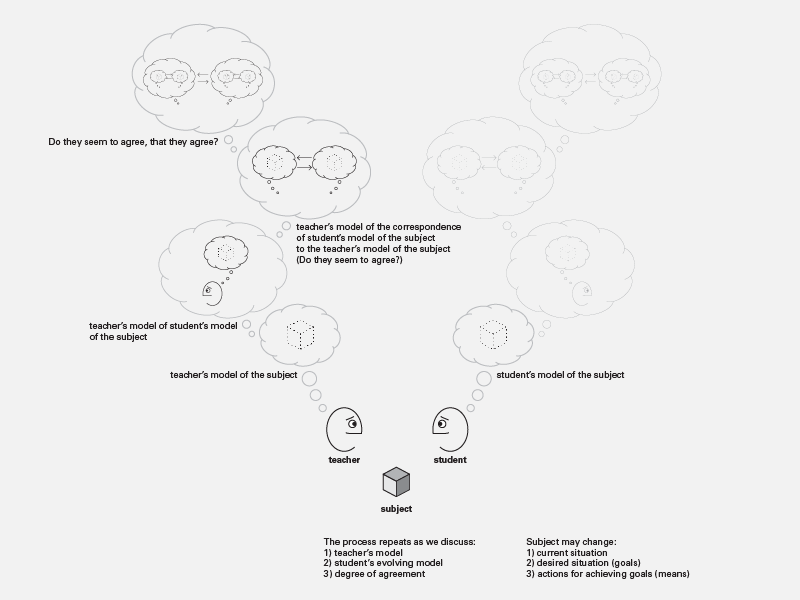

**9. Teaching + Learning as Conversation**

Two second-order systems interacting

Much of higher learning involves conversation—sharing + testing understanding in order to reach agreement. We might argue that all reasoned learning (anything above simple stimulus-response conditioning) is based on conversation, even if that conversation is with oneself.

Conversation is required to understand and integrate new information into prior models. (To put it another way: Conversation is required to change beliefs, and by definition learning is a change in belief.) For example, watching a videotaped lecture requires a student to focus on the topics being highlighted by a lecturer,

as well as to listen and understand how those topics interact—which of all possible aspects of each topic do

and do not relate to the points being made— to create a perspective or an idea that is new to the student.

The student literally re-makes the concept coming from the lecturer by taking different perspectives

that would arise if it were an actual conversation wherein the student and the lecturer re-constructed how the pieces fit together. The student learns the material by consciously running through how and why the topics are inter-related to create a new, coherent, complete concept.

As a result of the exercising of these perspectives, the student’s model matches the lecturer’s model to a sufficient degree to say that the student “understands” the material.

We might even say that mastering a discipline means entering into a series of conversations with members of the community that comprise the discipline—even if one’s access is restricted by place and time so that the conversation is essentially only within our imagination.

This model can describe the process by which an individual’s vocabulary grows—and the process by which a group increases the scope of language available to it (i.e., increases its “variety,” in Ashby’s terms).

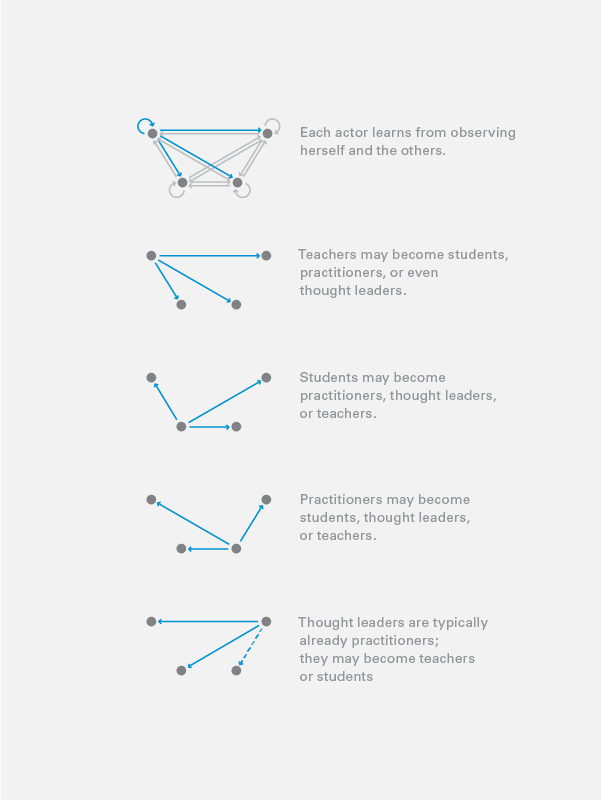

**10. Communities of Learning + Practices**

Embedding education in a larger system

Students learn from both teachers and other students. Students + teachers form “a community of learning”. When students graduate, they may join a “community of practice”. In a healthy discipline, the two communities are engaged in conversation: The community of learning teaches the community of practice; likewise the community of practice teaches the community of learning.

What is conversation? How can we design for effective conversation?

*Written for Interactions magazine by Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro.*

Interaction describes a range of processes. A previous “On Modeling” article presented models of interaction based on the internal capacity of the systems doing the interacting [1]. At one extreme, there are simple reactive systems, such as a door that opens when you step on a mat or a search engine that returns results when you submit a query At the other extreme is conversation. Conversation is a progression of exchanges among participants. Each participant is a “learning system,” that is, a system that changes internally as a consequence of experience. This highly complex type of interaction is also quite powerful, for conversation is the means by which existing knowledge is conveyed and new knowledge is generated.

Models of Models

*Written for Interactions magazine by Hugh Dubberly.*

Models are ideas about the world—how it might be organized and how it might work.

Models describe relationships: parts that make up wholes; structures that bind them; and how parts behave in relation to one another.