*Written for Interactions magazine by Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro.*

Interaction describes a range of processes. A previous “On Modeling” article presented models of interaction based on the internal capacity of the systems doing the interacting [1]. At one extreme, there are simple reactive systems, such as a door that opens when you step on a mat or a search engine that returns results when you submit a query At the other extreme is conversation. Conversation is a progression of exchanges among participants. Each participant is a “learning system,” that is, a system that changes internally as a consequence of experience. This highly complex type of interaction is also quite powerful, for conversation is the means by which existing knowledge is conveyed and new knowledge is generated.

We talk all the time, but we’re usually not aware of when conversation works, when it doesn’t, and how to improve it. Few of us have robust models of conversation. This article addresses the questions: What is conversation? How can conversation be improved? And, if conversation is important, why don’t we consider conversation explicitly when we design for interaction? This article hopes to move practice in that direction. If, as this forum has often argued, models can improve design, we further ask, what models of conversation are useful for interaction design?

We begin by contrasting “conversation” with “communication” in a specific sense. We then offer a pragmatic but not exhaustive model of the process of conversing and explore how it is useful for design.

What Isn’t Conversation?

—

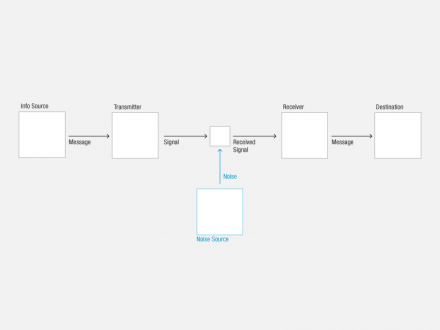

Claude Shannon developed a rigorous model of a transmission channel used to convey messages between an information source and a destination. While his context was analog telephones with wires highly susceptible to noise, Shannon produced a model that applies to a wide range of situations.

**Shannon’s Model of Communication:**

A message flows from an information source through a transmitter that encodes a signal.

The communication channel, shown as the tiny square box subject to noise,

conveys the signal to a receiver, which decodes the signal into a message

that is delivered to a destination.

In Shannon’s model an information source selects a message from a known set of possible messages, for example, a dot or a dash, a letter of the alphabet, or a word or phrase from a list. Human communication often relies on context to limit the expected set of messages. If you receive a call from a friend (the source) arriving by train, you expect to hear “I’m getting on the train,” or “I’m on the train,” or “the train is late,” and so on—messages that are drawn from a set of possibilities known to both of you. The channel is effective if it enables you (the destination) to select which of the possible messages is currently being transmitted. (Voice communication is more than sufficient for this, and Shannon’s interest was highly encoded transmission. But this simplified example draws useful distinctions for the discussion that follows.)

Communication in the sense of distinguishing among possible messages known in advance is important for much of our daily life. It allows us to synchronize a wide range of actions with others. But it has limits. Shannon’s model captures a fundamental limit of nearly all human-to-computer interaction: Our input gestures can only activate an existing interface command (select a message) from the preprogrammed set. While we can automate sequences of existing commands, we can’t ask for something novel. If our software application does anything novel, we file a bug report!

In Shannon’s model, how can we say something novel to one another? The answer is, we can’t. It’s not designed for that. We need the capacity for new messages to be generated and the resultant understanding confirmed or denied. We call interaction with these capacities “conversation.” Only in conversation can we learn new concepts, share and evolve knowledge, and confirm agreement. To describe how this works, we draw on the cybernetic models of conversation theory and Gordon Pask, because they are based on a deep study of human-to-human and human-to-machine interaction and because of their prescriptive power [2].

What Is the Process of Conversation?

—

Conversation at its simplest takes place when participants perform these tasks:

**1) Open a channel.**

When participant A sends an initial message, the possibility for conversation opens. For conversation to follow, the message must establish common ground; it must be comprehensible to participant B.

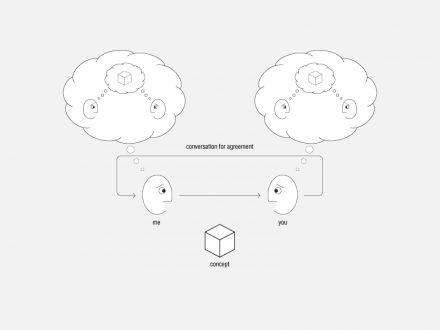

**Conversation for Agreement:**

As a result of conversation, participants agree on their understanding of a concept in that they share a similar model, and they believe that they agree.

**2) Commit to engage.**

Participant B must pay attention to the message and then commit to engaging with A. Such a commitment may amount to nothing more than continuing to pay attention. For conversation to persist, the commitment must be symmetrical, and either side may break off for any reason, at any time. Put another way, each participant must see value in continuing the conversation, which offsets the personal cost of being engaged: what we call the “bio-cost,” or the energy, time, attention, and stress required [3].

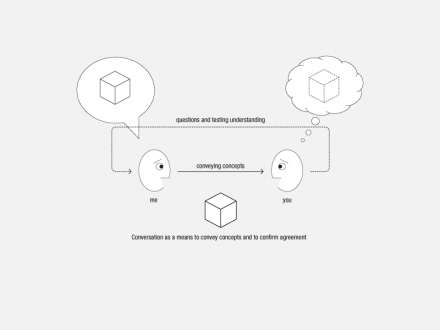

**3) Construct meaning.**

Conversation enables us to construct (or reconstruct) meaning, including meaning that is new to the destination. Conversation theory has a highly detailed model that we must leave to other descriptions though it is useful even in this skeletal form [4].

Messages are composed with topics or distinctions that are already shared, on the basis of prior conversation or shared contexts, such as common language and social norms. Participant A uses the message channel to convey what these topics are and how they are distinct from one another (descriptive dynamics), along with a kind of “glue” that explains just how these topics interact to make up the new concept (prescriptive dynamics). Participant B “takes all this in” and “puts it all together” to reproduce A’s meaning (or something close enough).

This can occur because, first, the descriptive and prescriptive dynamics come together to express an inherent coherence for the concept—they fit together like gears in a watch and only in a limited way or ways. Second, the human nervous system has evolved especially to make sense of the messages that arrive [5]. This “meaning making” (the taking all this in and putting it all together) is a mini AHA moment, every time we “get” what someone is saying [6].

**4) Evolve.**

Participant A or B (or both) are different after the interaction. Either or both hold new beliefs, make decisions, or develop new relationships, with others, with circumstances or objects, or with themselves.

Here we define an “effective conversation” as an interaction in which the changes brought about by conversation have lasting value to the participants.

**5) Converge on agreement.**

Participant B may wish to confirm understanding of A’s concept. To do so, B must create and transmit a different formulation of the topic(s) under discussion, one that captures his model of the concept. On receipt, participant A attempts to make sense of B’s formulation and compares it with her original intention. This may lead to further exchanges. When both A and B judge that the concepts match sufficiently, they have reached “an agreement over an understanding.” Such agreement may involve a fact about the world or merely shared belief. Sometimes participants agree on the qualities of a song, or that they like each other enough to continue talking.

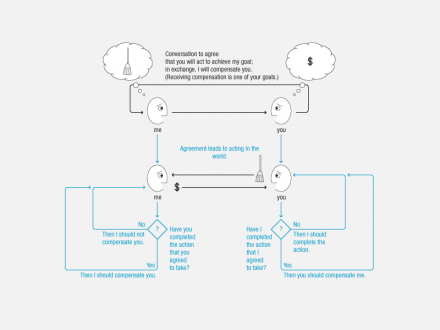

**6) Act or Transact.**

Sometimes one or more of the participants agrees to perform an action as a result of, and beyond, the conversation that has taken place. For example, they may agree to play a game together or enter into a relationship. Or they may agree to an exchange, as when money is traded for a product or service.

Thus we have a simplified description of conversation. All of us experience breakdowns in conversations; it is near miraculous that we understand each other at all. But if you comprehend this, the process of conversation is working right now.

What Does Conversation Offer?

—

Conversation enables participants to:

**1) Learn.**

We learn a great deal via conversation, including conversations with ourselves. We learn highly valuable life lessons, for example, ways to avoid being run over by a bus. At an opposite extreme, what we learn might seem simple: Our partner prefers drinking noncarbonated, room-temperature water; registering a credit card on a website saves time when buying airline tickets. Trivial as these examples may seem, learning basic things may save time later, freeing our future attention for other, less trivial, things. This is a valuable benefit of interactions that have memory and that evolve into relationships.

**Conversation to Learn:**

Conversation is a means to convey concepts and to confirm agreement.

When a conversation changes one of the participants, we say the participant has “learned.”

**2) Coordinate.**

We spend a great deal of time with others not merely synchronizing (“You’ve arrived, so let’s start!”), but also coordinating our actions in ways that are mutually beneficial. Anytime we negotiate one favor for another, we use conversation to reach an agreement to transact:

>”I’ll pick up the laundry if you stop for groceries, OK?”

“No, you have to take the car in for servicing.”

> “I can do both, but you’ll have to cook if you want to eat on time.”

“That still works for me.”

>”OK, good.”

In practice, society is a complex market of coordination based in conversation. Money is often used in the transaction, but not always. Subsets of the population agree to perform some actions (grow food, manufacture products, educate children, enforce the law) paid for by others who are free to do what they do, for (hopefully) mutual benefit.

Individuals and society become more efficient by coordinating work. This frees resources for other activities—including the design of more efficient products and services, in a recursive and generative process—which supported the Industrial Revolution. Conversation is the primary mechanism for complex human social coordination. It is a highly effective form of bio-cost reduction and therefore an engine of society.

**3) Collaborate.**

Coordination of action assumes relatively clear goals, but many times social interaction involves the negotiation of goals. (Horst Rittel believed this to be a fundamental challenge of design [6].) We may want to eat together, but one of us prefers Italian food, while the other doesn’t want to spend too much or listen to opera while eating. Or, we need to redesign our Web service but have conflicting demands for features, quality of experience, and development time. Or we would like to see a more equitable healthcare system. Conversation is a requisite for agreeing on goals, as well as for agreeing upon, and coordinating, our actions.

**Conversation to Coordinate:**

Participant B agrees to trade an action for payment from participant A.

B performs the action and confirms that his action has created the correct result.

A confirms her goal is achieved and compensates B as agreed.

Compensation may be monetary, return of favor, barter, etc.

What Are the Limits To a Conversation?

—

When designing for conversation, it is critical to consider what cannot happen. What can’t be talked about can’t be learned, conveyed, agreed on, or transacted. Conversations may be limited in two fundamental ways:

**1) Conversational infrastructure.**

We are frustrated when we can’t open a channel for conversation or when the channel is full of noise (experienced by every U.S. mobile phone user). Or we’re frustrated when we can’t use the available interface functions to get what we want. So, when software is the connection between participants, we ought to ask, “How well does the infrastructure support the conversational connection?”

**2) Conversational participants.**

Inherent in the capacities for a given conversation are the individual limits of its participants. Individuals contribute both what they know in depth and breadth and their style of interaction. Given a specific group of participants, conversations may go nowhere—they have no value; they create no lasting change in the participants. Other conversations create their own energy and go places—they are generative, have momentum, and lead to new and unexpected knowledge. We prize the individuals with whom we achieve this. “When assembling a design team we ought to ask, What expertise and what collaborative style(s) do we need? What variety is required to succeed?”

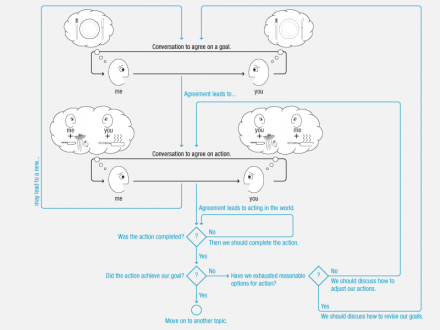

**Conversation to Collaborate:**

Agreeing on goals and coordinating actions to achieve them

Types of Participants

—

A human participant in conversation is usually a single person, although Pask suggests additional possibilities [7].

Conversations may take place between groups. For example, different political parties, religious groups, or nations interact with each other—they send messages, commit to engage (or not), evolve each other’s beliefs, and sometimes lead to transactions such as trade or war.

Similarly, we often have internal conversations—conversations with ourselves. I explore alternative perspectives, exchange points of view, come to a stable viewpoint about a belief or action (or, when I can’t, remain conflicted)—all inside my own mind.

We generate new ideas by combining old topics in new ways. This is important to interaction design because we spend so much time in front of screens talking to ourselves. Interaction design is as much about connecting humans across the murky “Internet cloud” (fostering community and conversation) as connecting an individual with his or her own capacity to explore what is possible and generate new possibilities (supporting internal conversations).

Why Does Conversation Matter?

—

Conversation matters to any community of interest (including our community of a single mind), but nowhere is the value of conversation more clear than in commerce, because commerce cannot flourish, or even exist, without conversation.

**Requirements for conversation**

>Establish environment and mindset—context

>Use shared language

>Engage in mutually beneficial, peer-to-peer exchange

>Confirm shared mental models

>Engage in a transaction—execute cooperative actions

**Marketplace example from user perspective**

>What’s new in mobile phones?

>How is this like a Blackberry?

>Can I use this in Europe?

>What will that cost?

>Yes, this product suits me.

>I accept your price and terms; here is my payment.

But many products and services, on the Web and off, connect individuals for broader reasons. Social networks such as Facebook and LinkedIn match two ends of a channel for mutual benefit, whether or not money changes hands. Sometimes what occurs is a sharing of interests, ideas, or even intimacy. But in all these cases, conversation is required.

Summarizing, conversation is infrastructure for commerce because:

+ Long-term success means ongoing commerce.

+ Ongoing commerce needs ongoing trust.

+ Ongoing trust is built via ongoing relationships.

+ Ongoing relationships are built via agreeing on goals and actions.

+ Agreeing on goals and actions is possible only through effective conversation. So, effective conversation is essential to commerce.

What Can Designers Do?

—

If conversation is important to “users,” we should explicitly model conversation as we design. Here are four broad proposals:

*View every user (persona) as a participant in a conversation, and every scenario as a conversation to define or achieve one or more goals. Use models of conversation to make design decisions, such as:*

1. What channel is being opened to begin the conversation? Is the interruption reasonable in how and when it intrudes? What is the bio-cost of the intrusion relative to its benefit? Are there better ways to interrupt?

2. Is the first message clear? Does it offer something to the recipient?

3. Once accepted, does the ongoing exchange convey the potential benefits in continuing the engagement? Is there learning or delight? Is curiosity or interest stimulated? At what bio-cost? How can it be improved?

4. Is meaning easily understood; that is, do the messages speak to the participants’ context, needs, interests, values, and in their language? How difficult is it for users to “put together”? How can messages be made more efficient or clear or entertaining, as appropriate?

5. How can users convey intention and meaning to the software? Are those means sufficiently expressive or easy or delightful? Where do they fall short?

6. Do participants evolve during the interaction? Aside from entertainment or delight, do they acquire something useful, learn a new point of view, or gain new knowledge? (This applies to human participants as well as software, which may evolve a model of the user for the sake of having more effective or more efficient conversations in the future.)

7. Do both sides agree? Can the participants agree to disagree?

8. Can sharing or exchange or transaction continue beyond this conversation, whether in the form of commerce or barter or simply agreeing to continue the conversation at a later time? In other words, has the conversation begun or continued a relationship?

*Invest in a better understanding of conversation:*

1. Review past projects and recast them as conversations: How could design outcomes be improved?

2. Look at new technologies or techniques in terms of conversation: Do they help generate more effective conversations?

3. When developing new projects, do models of conversation help in choosing technologies or techniques?

4. Can we design for conversations that directly improve trust, and therefore create stronger communities or greater lifetime customer value?

*Investigate trends, tools, and technologies that will change online conversations in the next five years:*

1. Personal journeys: How do physical age and technology exposure change predilections for media, modes of collaboration, and personal values?

2. Social computing: How will conversational technology transform individuals and organizations?

3. Portable and secure identity tools: How do OpenID and equivalents create secure and controllable online identities? How do they build trust? What can’t they do?

4. Cloud computing: How can we deliver the same experience everywhere, at lower cost?

5. Sensors: How does a seamless “network of objects,” when capable of conversational interaction, better extend our capacity for learning, coordinating, and collaborating?

*Invest in design of conversations via prototyping:*

1. For stakeholders: Build trust and value for employees, shareholders, clients, partners, competitors, and communities of interest.

2. Inside the organization: Instill coevolution as the process for understanding the market, defining and delivering the offering, and increasing customer satisfaction and shareholder value.

3. Across organizational and cultural boundaries: Explore a “marketplace of ideas.”

The Impact

—

Imagine a design movement that takes conversation seriously. Could it create a revolution?

The Industrial Revolution harnessed physical machines to extend and enhance our muscles. The Information Revolution harnessed virtual machines to extend and enhance our nervous systems. A “Conversation Revolution” would harness the existing infrastructure of physical machines and virtual machines to create a mesh out of “networks of objects” and networks of individuals and organizations. Such a mesh would enhance coordination and collaboration and create wealth by introducing new efficiencies. It would also expand opportunities to generate new knowledge.

Imagine a search engine designed for effective conversation, with all the knowledge on the Web participating. We would no longer be focused on “search,” nor would we be using an “engine.” What should it be called? Who will build it first?

19 Comments

Leonard Waks

Jun 10, 2009

9:58 pm

Fascinating article and so relevant to the new era of human-machine networks. Relevant to the study group on “listening” to which I belong

Peter Jones

Jun 11, 2009

5:22 am

This is interesting, but not exactly breaking news. I realize as working designers we re-invent and reformulate concepts for the new purposes (such as mobile tech). And this would be fine for a different publication.

However, interactions IS a professional journal. How could an article on designing for conversations not at least cite and reference Stanford’s Winograd, Berkeley’s Flores, and their work on the Coordinator from 1986? They not only wrote a book and peer-reviewed stuff, they built one of the first commercial email systems that embodied these principles (The Coordinator). There were debates for years in SIG CHI around that. And interactions is a SIG-CHI publication, yes?

And as scholars, their treatments cite and rely upon their sources for the conversation theory they embodied, Berkeley’s John Searle and his intellectual forebearer Austin.

I’m adding this comment because I believe it is critically important in the rapid-fire social media age to retrieve authenticity in our discourse that honors the legacies that led us here. Take an older friend to lunch this week and find out about their intellectual influences. And share them with others on the social media so we can enhance our collective wisdom.

Sam Ladner

Jun 11, 2009

11:45 am

I would have to agree with Peter on this one. Conversation analysis, ethnomethodology, or communicative action are other intellectual traditions that is worth investigating.

While I applaud interaction designers investigating communicative theory, robust mental models ought to embody the debates of the scholarly literature. So relying solely on a single notion of “what is a conversation,” limits what might be a very interesting approach to building interactivity.

Good work in pushing the boundaries of what interaction design ought to aspire to. I would encourage further theoretical debates to be embedded within actual designs.

Hugh Dubberly

Jun 12, 2009

6:03 pm

Peter –

Wonderful: a conversation about conversation! Thanks for posting.

You have us thinking about new possibilities:

– We’d like to solicit an article for “Interactions” on the history of conversation models.

Would you be willing to write one?

What models would you (and other readers) include?

– We’d also like to solicit an article looking at “The Coordinator” 20+ years on.

We’re hoping Terry Winograd might be willing to write that.

Now to the substance of your post: We accept your point that our article should reference Winograd and Flores. That’s an oversight, at least partially corrected below. Your further suggestion, however, that our article “re-invents and reformulates” their work misses the point of both their work and ours.

Winograd and Flores work is important, because it offered a new way of looking at “computers and cognition”, challenging the flawed orthodoxy of artificial intelligence. Within that context, the authors also developed a model of the possible sequences of interaction between participants in what they termed “conversation for action,” essentially a highly constrained (and somewhat mechanistic) view of coordination, itself one portion of the larger space of conversation. The authors needed to take a narrow view of conversation and coordination in order to model it in software, “The Coordinator”, another important achievement in their work but one limited by the software systems of the time.

We acknowledge that The Coordinator was an important advance, but we advocate an approach to “designing for conversation” which differs in at least three fundamental ways:

1) A robust model of conversation must include participants’ goals.

2) It must also acknowledge the central role of processes that build understanding and agreement.

3) And it must, at every level, allow for the possibility of true interaction (e.g., negotiation of goals and actions) between participants.

Of course, that’s the essence the models articulated in Pask’s “Conversation Theory.” Here, we should further acknowledge the shared roots of Winograd and Flores’s work and that of Pask. Both are grounded in the second generation of cybernetics. Both reject notions of “objectivity;” both embrace the subjective role of observers and frame observers as participants; both owe a debt to the work of Heinz von Foerster.

For readers interested in more information, please see

Winograd, T., and Flores, F., Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design, Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park, 1986.

Ranulph Glanville

Jun 16, 2009

8:35 pm

I do a lot of refereeing of papers, and have found it important to be rather cautious about insisting on priority and key references. In my experience, there is always another set of possible references, and there is always an antecedent. In the case of conversation, Pask was publishing his explicit theory in the early 1970s. In the 60s and 70s, he was a regular visitor at MIT and at Project Mac, and knew and influenced Winograd, as he was also a visitor to Allende’s Chile and knew Flores (I was detailed by Pask to drive Flores around London as a sort of taxi, when he escaped Chile and was in town: Flores was deeply ungrateful and ungracious).

But Pask was doing conversational stuff earlier. His 1961 book (An Approach to Cybernetics) is full of reference to conversation (I have published on this, but only in German), and his earlier work is interactive in a much richer sense than almost anything since: a manner that is truly conversational (conversation being essentially interactive).

Pask wrote about the use of conversation in a similar manner to some of the use in this paper, in “The Architectural Relevance of Cybernetics” (1969).

Pask and I discussed design over the years from 1967 until his death, and played with several ideas. I have published on the centrality of the conversation with the self, as being at the heart of design. But I didn’t publish this till later.

There are always precedents, And there are always precedents that occurred before the precedents I (or you) cite. It’s nice to have Winograd and Flores brought into this rather under-referenced piece above, but they really aren’t the origin and it’s a shame that their inclusion is proposed in the manner in which it is.

Peter Jones

Sep 14, 2009

5:29 am

Hugh, although we’ve talked in person about this discourse since, I never revisited the commentary. I missed Ranulph’s comments and personal insights, and what a miss it was.

A fascinating story about Flores in London after his escape from Chile post-Allende. he was a formidable personage in his times and places. He has been in Chile this decade as I understand, after disengaging his seminal firm Business Design Associates at the end of the last decade. While not the inventor of most of the work he’s known for, Flores was the innovator, in the sense of creating products (Coordinator) and systems (independent educational programs) that advanced and embodied these ideas. As second order cybernetics suggests, we need to re-enter our practices with our own theories, intervening rather than observing to understand.

A journal like Interactions is primarily practice-focused, so my pique about the miss on Flores was overtstated. It doesn’t matter that much in scholarly terms, because you’re spot on about the precedent. But I’m more interested in legacy, as perhaps you are. The Coordinator just has a huge legacy for its audacious early entry into constructing an interactive world of its own conversational theory. Although there was plenty of heat discussing it in the ACM world – mainly after it died – We also should have learned more from its innovation than we did.

Our current email ecology is a weak transaction oriented system that we have adapted to, rather than adapting to conversation. (And gmail is not that innovation we were waiting for either).

Pask was a deep influencer and should be cited more than we find in published articles. I’m reviewing second-order cyber papers for another piece and I do notice where he’s missing now, where I would have not before this discussion. But then, Jantsch, Ozbekhan, and Dervin don’t get cited for their early influence work either. Its helpful to notice, their ideas stand the test of time.

nida

Jul 6, 2011

5:57 am

i find the article very constructive and definitely will be useful for my introduction communication lesson. thank you.

Ayesha Vemuri

May 29, 2012

5:24 am

An extremely insightful article and discussion on the design of conversation. I’m particularly interested in this topic because I work for a design innovation organization in India that will be organizing a conclave on this very topic in December.

We were talking, at the last Design Public in April, about the need for conferences, conclaves and meetings to be designed more intelligently so that they yield true meaning and value, and don’t just devolve into Babel-like cacophony, or stop at the voicing of problems and barriers, of which there are always plenty.

It was interesting to see the stages, or process of a conversation, especially the evolution part. How can you design a conversation so that it actually evolves? Can it really even be done? I’d appreciate your thoughts.

kamal

Jun 24, 2012

12:04 pm

thank you so so so so much

babu pinieli

Dec 6, 2012

2:10 am

im interested in tthis tropic also because i understand well on conversation together with my friends. thank you.

Nicola

Jan 17, 2013

3:10 am

THIS IS FANTASTIC

Desmond Sherlock

Jan 20, 2013

3:08 am

A very interesting post.

I have been working on this question of what conversation is to me for some 25 years and answered it only recently.

I think that conver-sation is a process of conver-ting our own concepts, through peoples feedback, into agreements and possible solutions.

As you mentioned above a conver-gence of ideas into an agreemet.

I have developed 6 rules of engagement that my brother and I have agreed to use and it seems to act as a counter balance to help moderate our disputes.

Carl Garcia

Sep 19, 2013

1:26 am

This is so very interesting to me, because I have actually developed such a technology!

It is essentially a conversational technology that coordinates actions between two or more parties when a particular goal is clear. The outcome eliminates “the noise” that occurs in such an exchange under a normal conversation. When used with a QR code, it can be associated with a context in the real world and the data collected is persisted in the cloud for historical analysis.

Please see the video on our site. We’d be thrilled to hear your opinion.

Carl Garcia

http://www.nextideatechnologies.com

Saroj Thakur

Aug 18, 2014

3:00 am

A very informative article. Would be using it in my class! 🙂

Maria Mwafulirwa

Mar 16, 2015

3:55 am

Discuss exchange models of communication and how they apply to every day life?

ismaaciil aadam

Aug 18, 2016

10:17 am

coverstion makes the person more confidential more experience

Joyce L. Juster

Dec 6, 2016

11:58 am

This is an awesome article!!! Conversations are not just the words but the intent to leave each individual informed and different in some way than how they were at the onset is exactly what the ancient Greek Forums intended. To entertain a question or an observation and at the end the conversation you could say “converted” one’s way of seeing to a different way of seeing. Thank you so much!

Hussein Hassan

Dec 23, 2016

11:32 pm

dears ?

can anyone of you send me some sources about conversation, it is definition and components.

Apollo Pawangan

Mar 28, 2021

8:27 am

What is seamless conversation?